Why does your experience and opinion matter?

In a short answer, because that’s how learning happens best. No matter what your instructor’s philosophy of teaching, if they are using this textbook you can probably assume they agree with us, Kohn and countless others who believe that learning happens constructively, or through a “constructivist approach,” that always has to involve students.

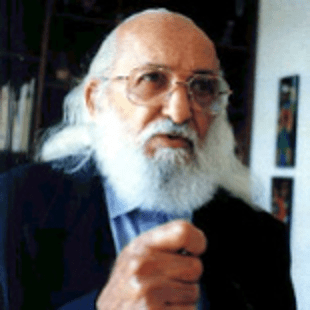

Our constructivist teaching and learning philosophy is influenced by the work of Paulo Freire, who is known as the father of “student-centered” teaching and learning. Freire was an activist and teacher of adult reading in Brazil during a time when workers’ rights were being massively exploited, largely because they were uneducated. Without being able to read, these impoverished workers could not negotiate contracts or learn about how to defend their rights.

Freire called this “reading the world,” which is the premise of this text and many of the projects involving student choice in our curricula across SFSU and beyond. In Freire’s critical pedagogy, or radically progressive way of teaching, the curriculum is framed around the students’ worlds, involves their real issues, desires, and needs, and the teacher can learn from the multiple literacies of the students’ worlds even as they teach them more traditional literacies in school.

Freire made learning to read a very political and liberatory act in ways that many will never understand today, as most of us are lucky enough to be taught basic comprehension in elementary school and don’t give much thought to the act of reading after that, except as a chore for school that it usually becomes around junior high.

To counter this trend where reading becomes a chore and learning becomes boring, we take constructivist teaching and learning further, where we borrow from Alfie Kohn who frames learning around “deep questions” generated by students. By doing so, Kohn believes that students will be motivated to learn based on genuine curiosity, problem solving, and a curriculum that revolves around their lives. Kohn frames it best by saying, “By contrast, the best sort of education—which is not only more respectful of children but far more effective—takes its cue from the interests of those who are being educated. The center of gravity is the kids; their purposes and interests are our point of departure” (3).

We know the readers of this textbook are not kids, although your purposes and interests are our point of departure. Our goals are to introduce you to the process and practice of reading and writing in a deliberative, critical, and “metacognitive” approach. While these words may be new to you now, the main idea is that embracing this approach will help you take control of how you read and write best. To accomplish this, through this textbook we invite you to take an active approach to your own learning, based on a few premises that we will cover with you interactively (with more Discussion Forums and hypothes.is annotation prompts) in the following pages.

These premises are:

- Everybody learns differently. All students, and teachers, bring different strengths to the classroom, and reading and writing processes should be taught within a “pedagogy of multiliteracies”* to reflect multiple learning styles and create inclusive learning environments. The interactive exercises and approaches in this book are intended to help you find out how you learn best: linguistically, literally, visually, kinesthetically?

- Learning must be challenging, and knowing yourself as a learner gives you the power to set your own level of challenge, as well as seek appropriate resources.

- Everybody has the capacity to learn, and by internalizing a flexible “growth mindset” where learning happens through sustained, deliberate practice in collaboration with others, all readers and writers grow. This includes us, very much so, through the writing of this textbook!

- Who you are as a learner matters! And there are many opportunities in college to explore various Discourse Communities and other communities of practice, including various cultural resources local to your new community, to make the most out of your college experience – for you.

- Last premise, and maybe the most important, is: You don’t have to do it alone! To reinforce our own ethos as educators, we have SFSU faculty spotlights discuss the best ways to advocate for your own learning as college students and community members.

* Serafini and Gee cite the New London Group manifesto, “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies” (1996), who reinforce the ethos of much of this textbook, when they write that the Group “…recognized the importance of multiple modalities in meaning-making as well as the value and necessity of diversity in representations of meaning-making, whether that be specialist forms of language used by scientists or the mixture of text, visual images, or video on a pop-culture fan website” (3).